One actuary says social and technological factors are changing the concept of retirement, while another notes the fundamentals remain the same.

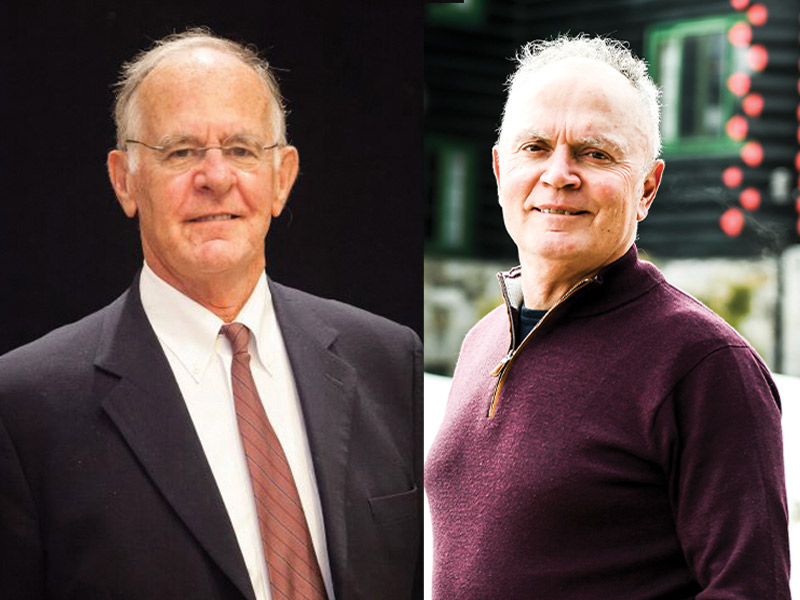

Michel St-Germain, retired actuary, fellow and past president of the Canadian Institute of Actuaries

Yogi Berra once said: “The future ain’t what it used to be.”

Millennials will be retiring in 25 years, but not in the same way as current retirees. Retirement is no longer about stopping abruptly at a fixed age — yet our retirement system is still designed on how older workers were retiring.

Read: Survey finds 74% of Canadians aged 24 to 44 view conventional retirement approach as outdated

Older workers are working longer — since 2000, among employees aged 65 to 69, participation rates have doubled for males and tripled for females. Remote work is now common, with more flexibility and reduced stress, while artificial intelligence is changing how we work, creating new types of jobs.

Retirement planning will have to consider employment income after age 65 as more employers may consider retaining older workers. Indeed, policymakers may have to change the design of defined benefit pension plans and government plans to adapt to the new workforce.

The cost of encouraging workers to retire early while there are labour shortages and available jobs is a poor allocation of retirement dollars. The savings from reducing those incentives could be used to provide higher benefits for those who work longer or higher wages for all. In addition, too many Canadians elect to receive Canada Pension Plan/Quebec Pension Plan benefits at age 60, even those with employment income. A higher minimum age could be considered. QPP can now be deferred to age 72. The government could also increase the maximum age for CPP and old age security.

Read: Helping employees understand the benefits of delaying CPP/QPP

The maximum age to begin registered retirement income fund withdrawals could also be increased from age 71 to reflect increased longevity. As well, DB plans could provide more flexibility by allowing partial withdrawals to reflect part-time work after age 65 until complete retirement.

Fred Vettese, author and pension expert

Society has an inherent distaste for words that denote something that’s deemed undesirable, inferior or unfortunate in some way.

I could give examples, but that would require me to identify a word that was taken out of circulation, something we tend not to do in polite society. The question is whether the word ‘retirement’ should be added to the list of euphemized words.

Read: Can IBM’s retirement benefit account revive the traditional DB pension plan?

It’s easy to see why many older people shun the word. Being retired might suggest a waning of energy or ability that renders one less capable than they were ten or twenty years earlier. This concern with the word is not new. I recall many conversations as far back as the 1990s with people who were no longer working full time at a ‘regular’ job. Rather than saying they were retired, they described themselves as self-employed or working as a consultant.

This isn’t to say that nothing has changed in the intervening 30 years. Today’s 60-somethings are much more likely to phase out of work gradually, but they still do retire. It’s just that the line between working and not working has been increasingly blurred. The day still comes when the vast majority cease to work for money (Mick Jagger being the exception). At that point, we could invent a new word to replace retirement but that new word will eventually take on the same taint of referring to something that is undesirable, inferior or unfortunate.

What is important is to accept that planning for retirement (or whatever we choose to call it) is little changed from what it was in a previous generation. If anything, it has become more important. With the near-disappearance of DB pension plans in the private sector, individuals have to take on more responsibility for saving enough and investing appropriately and, when the time comes, for turning those savings into income that lasts them a lifetime.

Blake Wolfe is the interim editor of Benefits Canada and the Canadian Investment Review.