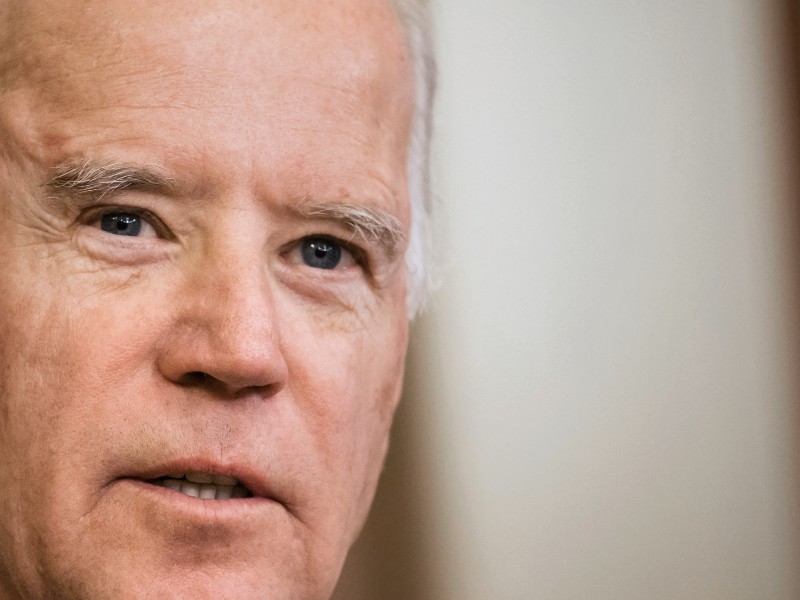

Former vice-president Joseph Biden will inherit an economy beleaguered by the battle against the coronavirus if he wins the election in November. The recession will influence his legislative priorities in both the short and long term; however, Biden has indicated that he would raise an array of corporate and personal taxes to finance domestic programs, including social security, health care, green energy and infrastructure projects.

Biden’s tax plan would restore many provisions of the tax code in effect prior to passage of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, netting approximately US$3.8 trillion in new federal revenue over 10 years. The corporate rate would rise to 28 per cent from 21 per cent, still below the 35 per cent pre‑TCJA rate. The administration would seek to double the tax on Global Intangible Low‑Taxed Income, which would bring the total rate up to 21 per cent—affecting companies that generate offshore profits and benefit from tax arbitrage.

Biden’s plan also includes a minimum tax on corporate income, which would affect businesses with book profits of US$100 million or higher. The tax is structured as an alternative minimum tax, in which corporations would pay the greater of their regular corporate income tax rate or the 15 per cent minimum rate. Businesses would still be permitted to deduct net operating losses and receive foreign tax credits.

Uncertainty remains regarding how many of these tax proposals would become law, or whether Biden might modify them given the global recession and legislative compromise.

Biden’s individual tax plans primarily target both the highest‑income earners and those who derive their income from investments. The Biden plan would revert tax rates to the pre‑TCJA rate of 39.6 per cent, affecting earned income above US$400,000. The plan would implement a 12.4 per cent social security payroll tax on earned income above US$400,000, split evenly between employers and employees in order to fortify the social security system and increase benefits for retirees at lower income levels.

Biden would also phase out the 20 per cent qualified business income deduction (including qualified real estate investment trust dividends) for filers with taxable income above US$400,000, and cap itemized deductions to 28 per cent of value—mostly affecting those in the top tax brackets.

The Biden campaign’s wish list also includes plans to increase taxes on long‑term capital gains and qualified dividends. Here, too, the greatest impact would fall on the wealthiest taxpayers.

Additionally, Biden would eliminate the step‑up in cost basis for assets left via inheritance. Currently, the cost basis steps up to the value of the asset at the time of the donor’s death. If this proposal were enacted, the inheritor would retain the donor’s original and presumably lower cost basis—generating a larger capital gain if the assets were sold.

David Giroux, T. Rowe Price chief investment officer of equity and multi‑asset and head of investment strategy, estimates the rate increases would collectively reduce S&P 500 company profits by nine to 11 per cent. However, some industries could benefit from increased spending and I believe that a few sectors and companies may see fewer adverse effects.

An increase in tax rates would have less impact on earnings per share for utilities because taxes are passed on to customers. Energy exploration and production companies generally pay relatively less in cash taxes and so would benefit relative to other sectors. But these companies could be subject to the minimum tax rate provision, which would put pressure on utilities’ customer bills and rate base growth while potentially affecting energy companies in a higher‑price environment.

Non-U.S.-domiciled companies would also escape a higher GILTI rate, since the provision only applies to U.S. companies—though only 2.9 per cent of the S&P 500 is domiciled overseas.

Whether such tax proposals are enacted hinges heavily on the outcome of Senate elections. Democratic control will be critical in determining not only how much of Biden’s legislative agenda would become law, but also the degree to which his priorities may have to shift to bring Republicans to the table. A tighter margin in the Senate means that more controversial provisions, like the corporate minimum tax, would be more difficult to accomplish.

The two most important factors in projecting the trajectory of Biden’s legislative agenda will be the state of economic recovery and the coronavirus, especially early in 2021. Were the country to continue to experience widespread spikes in infections amid social distancing, the path to recovery would be even more difficult to discern. A higher risk of crisis would make another deficit‑funded stimulus bill more attractive, resulting in the delay of tax rate increases until the economy is on more stable footing.

Katie Deal is an analyst in the U.S. Equity Division of T. Rowe Price covering Washington research. These views are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Canadian Investment Review.