PARTNER CONTENT

Emerging markets are a dynamic and evolving asset class that give plan sponsors access to growth companies, as well as exposure to mega trends like technological innovation, the rising consumer and green transition. We asked five expert panellists to discuss emerging markets’ opportunities and risks.

Meet our expert panellists

Romina Graiver

Partner and portfolio specialist,

William Blair

Navin Hingorani

Portfolio manager,

Eastspring

Andrew Keiller

Partner and investment specialist director,

Baillie Gifford

Roderick Snell

Partner and investment manager,

Baillie Gifford

Vivian Lin Thurston

Partner and portfolio manager,

William Blair

How are interest rates and higher inflation in the United States and other developed countries impacting emerging markets?

Vivian Lin Thurston: In a rising interest rate environment, discount rates across asset classes tend to rise. This definitely impacts the equity class more than other asset classes because cost of equity tends to be more asymmetrically affected. This also hits growth equities harder, as growth companies tend to have a longer duration of cash flow generation. But the impact of inflation we’ve seen in emerging markets is less than in developed markets—inflation on wage and goods caused by reopening and price inflation due to the Ukraine war were not as acute in emerging countries.

Roderick Snell: What’s interesting is what hasn’t happened in emerging markets. Typically, rising inflation and rate hikes lead to a higher dollar and suck liquidity from the region, creating your typical emerging markets crisis. However, this time we’ve had the dollar on an absolute tear, reaching a nearly 40-year high. But emerging markets are in a much better macro position than developed countries. They have stronger balance sheets because they didn’t print money during COVID; and they’ve had, and still have, sensible real interest rates for many years. There hasn’t been a major inflation issue and they don’t have the same supply chain problems. This cycle, the West has been unorthodox, behaving like the emerging markets of old—whereas emerging markets behaved relatively conservatively.

Navin Hingorani: The largest sector in the emerging market index is financials, and now you’re seeing tailwinds from higher rates. Within developed markets, interest expenses are up almost 40 per cent year on year; and the interest expense in emerging markets is up around 20 per cent year on year. I’m optimistic about the health of companies within emerging markets and their ability to handle inflation and higher interest rates.

Romina Graiver: Another key point is where we are now in the cycle. Emerging markets started with a base where inflation was less of an issue and they were more proactive in dealing with it. However, like developed markets, it’s rolling over now. We saw Chile and Brazil cutting rates and others will likely follow. Of course, China is a separate case in this particular situation, but it’s quite unusual to see emerging markets lowering rates while developed markets are still hiking.

The largest sector in the emerging market index is financials, and now you’re seeing tailwinds from higher rates.”

— Navin Hingorani

What opportunities do you see in developing economies from the global adoption of artificial intelligence technologies?

Andrew Keiller: Everyone seems to have become an AI expert over the last six months, so we do need to be cautious in differentiating hype from reality. But in general, we would expect emerging markets to provide the “picks and shovels” of AI infrastructure— and that’s the way we’ve aligned our portfolio. AI isn’t the only demand driver for these long-standing holdings though. You also need to think beyond the hardware companies to some trends that might be less obvious. We’ve thought a lot about the Indian IT outsourcers; many sell-side researchers are negative, saying AI is a big threat to these companies, but we believe AI might be a big opportunity here. They will likely have a role helping companies adopt AI and use it effectively.

Andrew Keiller: Everyone seems to have become an AI expert over the last six months, so we do need to be cautious in differentiating hype from reality. But in general, we would expect emerging markets to provide the “picks and shovels” of AI infrastructure— and that’s the way we’ve aligned our portfolio. AI isn’t the only demand driver for these long-standing holdings though. You also need to think beyond the hardware companies to some trends that might be less obvious. We’ve thought a lot about the Indian IT outsourcers; many sell-side researchers are negative, saying AI is a big threat to these companies, but we believe AI might be a big opportunity here. They will likely have a role helping companies adopt AI and use it effectively.

Lin Thurston: Because it’s a closed system, China will be on its own when it comes to AI. This is similar to what we’ve seen in the past, whether it’s search, ecommerce, online gaming or social media. China has tried to catch up quickly with AI, so there’s the possibility it will develop their own and continue to evolve— especially in areas where they can find new connections between technology, adoption and applications.

Hingorani: Investors entering this arena need to be careful, focusing on the returns being assumed for companies and how long those returns can be generated. However, this is also an opportunity because IT is prominent in emerging markets—it’s 20 per cent of the EM index and 27 per cent of the EM ex China index. There are going to be first-order effects from any AI adoption going forward; and then there will be second-order effects that play through to those other sectors and EM economies, too.

How can plan sponsors take advantage of India’s booming manufacturing and IT sectors? Are there other areas of the Indian economy you think hold promise?

Snell: For the first time ever, we’re seeing innovative tech businesses in India that came about from the increase in cheap smartphones. There are direct plays people can take: Policy Bazaar, the country’s leading online insurance broker—or Delhivery, the largest private sector logistics company. A lot of innovative Internet businesses are currently private, but over the next three to four years we expect tech companies worth $300 billion to $400 billion will enter the public market, transforming the opportunity set in India. There are also early signs India might be building a successful export manufacturing industry, thanks to a number of government reforms and the establishment of several economic zones. Foxconn, the Apple iPhone manufacturer, is expanding dramatically in India and iPhone exports quadrupled to about $5 billion for the 2022/23 financial year.

Hingorani: There are a couple of other sectors where we see good opportunities. The Indian financial space is one of the sectors that hasn’t run as much as others; we’re finding value in mispriced stocks because of the market’s assumptions about their credit books or management concerns. We also see potential in the property sector; we’ve seen relatively flattish volumes and prices, but this is a market where the urban population’s income is growing.

Lin Thurston: The consumer is a big driver in India. We see a lot of investment opportunities in consumer goods, retail, travel, consumer-driven financial services and more. But there’s a valuation risk: Indian equities are not cheap. This due to structural reasons—both because of its strong secular growth story and the scarcity of certain equities. There’s also the dynamic between Chinese and Indian equities; when Chinese equities are unfavourable we tend to see a lot of flow into Indian equities, which would probably expand that premium. Over the long term, Indian equities’ high multiples will likely be supported by the country's secular growth story. We just need to be more selective.

There are also early signs India might be building a successful export manufacturing industry, thanks to a number of government reforms and the establishment of several economic zones.”

— Roderick Snell

What should plan sponsors know about capitalizing on the demand for semiconductors?

Snell: As semiconductors become more advanced, we’ve seen massive consolidation—with only a few companies staying in the race—and it’s very profitable. The automotive chip space is an important driver of that profit. When it comes to individual stocks in emerging markets, we generally prefer those that serve broader end markets and aren’t reliant on a single industry. TSMC plays on anything from electric vehicles to the Internet of Things. Likewise, in computer memory, Samsung and SK Hynix are the leading players, with Samsung also conducting business in logic chips. Also, given tensions between the U.S. and the West, China needs to become self-sufficient in semiconductor technology. One of the ways to do this is via businesses like Silergy—one of China’s top analog chip suppliers.

Snell: As semiconductors become more advanced, we’ve seen massive consolidation—with only a few companies staying in the race—and it’s very profitable. The automotive chip space is an important driver of that profit. When it comes to individual stocks in emerging markets, we generally prefer those that serve broader end markets and aren’t reliant on a single industry. TSMC plays on anything from electric vehicles to the Internet of Things. Likewise, in computer memory, Samsung and SK Hynix are the leading players, with Samsung also conducting business in logic chips. Also, given tensions between the U.S. and the West, China needs to become self-sufficient in semiconductor technology. One of the ways to do this is via businesses like Silergy—one of China’s top analog chip suppliers.

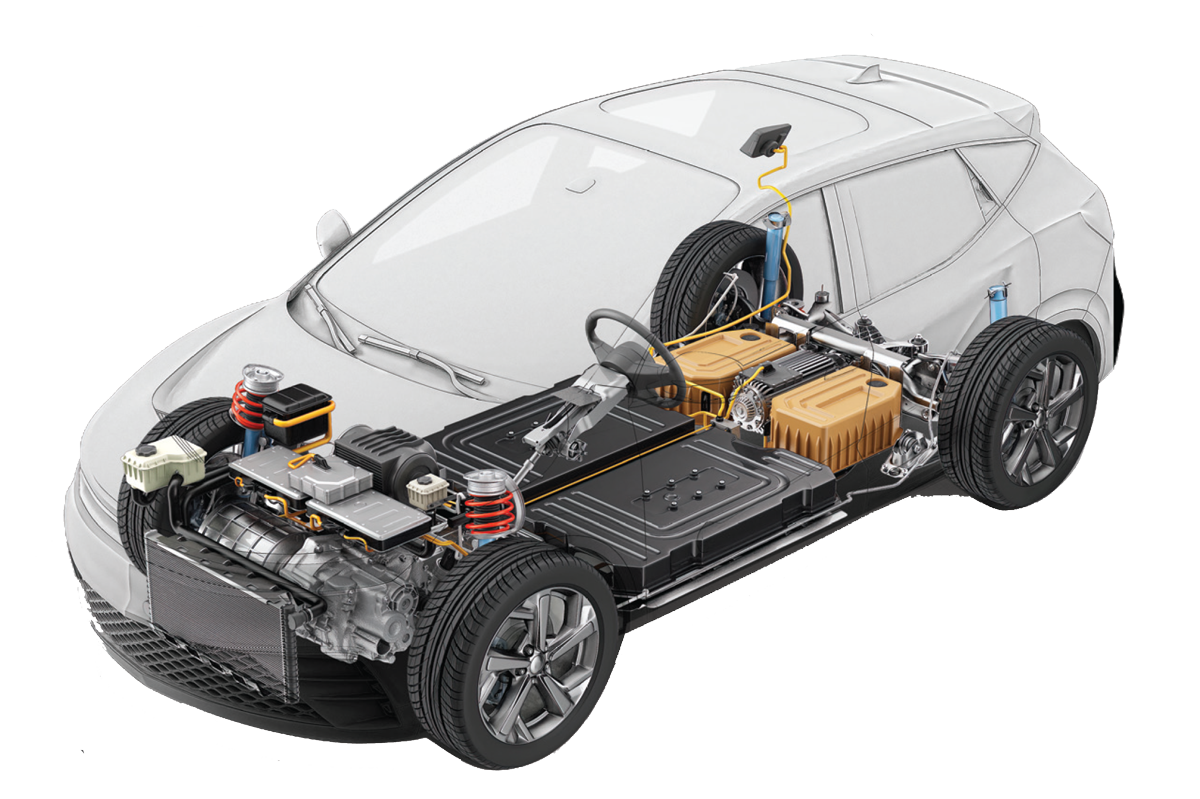

Graiver: The increasing amount of semiconductors required, as demand for electric and autonomous vehicles continues to grow, is going to be tremendous. EV semiconductor requirements are at least double those of internal combustion engine vehicles—and the numbers are even higher for autonomous vehicles. Many automotive chip companies are developed market companies, so there’s more focus on TSMC companies and their supply chains.

Lin Thurston: From a structural demand perspective, we see a shift from a big smartphone market to a broader one. Before generative AI, semiconductor demand globally was not as positive in comparison to the last 10 to 15 years. Smartphones are the best type of end markets, given the smaller purchase prices, faster upgrades, shorter product cycles and higher value content. And as smartphone growth slows down and becomes a less important driver, the support for global semi demand is difficult to replenish — even by EVs. Now with generative AI, I think there's a good chance demand could be supported on a structural level. But I think it will also increase the cyclicality of the industry. That’s why you’ll see different semiconductor suppliers in Taiwan or Korea—depending on their end market, they’ll have different earnings cycles.

With the world’s green transition, what markets do you see as potential winners?

Snell: China is a winner here. Because of its huge domestic and industrial policies, it’s already become the global leader in several green technologies. It’s the world’s largest producer, consumer and exporter of EVs, accounting for about two-thirds of global EV battery production and 80 per cent of solar panel production. We’re also excited about the opportunities in other countries supplying the raw materials. In Asia, I think Indonesia is the most interesting, given it accounts for about 20 per cent of the global nickel supply. It banned the export of raw materials several years ago, so everything has to be processed in the country. This means it’s able to capture even more of that value chain.

Hingorani: Green infrastructure is commodity intensive. EVs use six times more minerals than combustion engines; and wind and solar require more minerals than coal and gas. Emerging markets are the home for commodities—like Indonesia and the Philippines for nickel; lithium in Latin America; and platinum in South Africa. And because of this, these countries are going to be natural beneficiaries.

Graiver: When it comes to the minerals and metals necessary for the transition, there are concerns over whether private companies are going to be allowed to have those outsized profits or if there’s going to be more resource nationalism and government interference like we’ve seen in Chile’s approach to lithium. Given this, we see active management and good stock selection skills being paramount when plan sponsors think about EM.

Is the growing trend of resource nationalism around minerals, microchips and the green transition influencing your EM investment strategies?

Hingorani: I think it’s important to look more broadly and think about how other aspects related to the green transition or carbon pricing are going to impact a company’s returns. We’ve spent a lot of time thinking about specific industries, where costs are likely to be incurred into the future that aren’t being incurred at the moment.

Hingorani: I think it’s important to look more broadly and think about how other aspects related to the green transition or carbon pricing are going to impact a company’s returns. We’ve spent a lot of time thinking about specific industries, where costs are likely to be incurred into the future that aren’t being incurred at the moment.

Snell: We do certainly consider access and resource availability as part of any investment case. Chinese companies certainly stand out as being well placed; the country probably has a 10- to 15-year edge when it comes to the mining and processing of critical raw materials. China processes about 60 per cent of all lithium globally; and the European Union currently imports about 93 per cent of its magnesium and about 85 per cent of its rare earths from China. As China looks to invest and secure the supply chain further, this can be a major boon for other countries. China has recently built plants in Indonesia that can transform non-battery-grade nickel (used for stainless steel) into battery grade nickel. As China secures nickel suppliers, the world’s leading supplier of non-battery-grade nickel can convert a large portion to battery-grade—and this could be transformative.

Graiver: I think this is part of the increased complexities that EM managers need to navigate around nationalism and geopolitics, whether it’s resource nationalism, Europe’s supply chain transparency requirements, the Inflation Reduction Act or the CHIPS and Science Act that will put limitations on Chinese semiconductor manufacturing and research. These can be headwinds but also tailwinds for companies benefiting from these policies. This is part of the case today and will likely be ongoing.

What impact are you seeing from shifting global supply chains in Latin America and Asia — and China in particular?

Lin Thurston: Many U.S. companies are starting to move their supply chains away from China—to northern Mexico, Southeast Asia or even India. This is driven by the supply chain disruptions seen during COVID, making them realize the value in physical proximity. Further, geopolitical tensions made them feel the higher political risks when sourcing from China. Mexico is also economically favourable, as labour costs are cheaper and there are tariff breaks from the new NAFTA. Certain Chinese companies have also set up factories in Mexico to target the supply chain market in the U.S.

Hingorani: China used to have a labour cost advantage that has since disappeared compared to other emerging markets. China is having to contend with an aging and decreasing population, as well as economic and political measures coming out of the U.S. I think there’s going to be a structural change when it comes to supply route diversification, driven by political and economic tension. For a lot of these other economies, a small shift away from China and towards themselves can make a huge impact. Since 2017, foreign direct investment in ASEAN countries has more than doubled—and India, the C3 countries, Turkey and Egypt are likely to be beneficiaries, too.

Graiver: None of these countries can fully replace China. The need for diversification, which became more prominent because of COVID and continued amid geopolitical tensions, was required to some extent, but is adding inefficiencies and cost. This is good news for countries that received foreign direct investment, but China has tremendous advantages in terms of scale and infrastructure. This allows for the optimization of logistics and production processes that may have more challenging effects for the global economy overall.

Snell: As people look to diversify supply chains, Vietnam will be the clear beneficiary. I believe Vietnam, currently a frontier market, will be the best structural growth story of any country over the next 10 to 20 years because it’s successfully leveraged its young, cheap workforce. In addition, Vietnam has also capitalized on its government’s ability to get things done to build a successful export manufacturing base. With somewhere around $2 trillion of low-end manufacturing coming out of China and up for grabs over the next decade or so, there’s a good chance a large portion will go to Vietnam.

China has tremendous advantages in terms of scale and infrastructure. This allows for the optimization of logistics and production processes that may have more challenging effects for the global economy overall.”

— Romina Graiver

Should Canadian pension plans be worried about ongoing tensions between the U.S. and China?

Hingorani: In every crisis there’s an opportunity. It’s very easy for the market to fall out of love and start pricing things at a level that isn’t reflective of a company’s potential returns. We see a lot of opportunity in China due to sell-off at a broad level.

Lin Thurston: The U.S. and China have entered a new relations era as strategic competitors. This has led to the increased risk premium of Chinese equities and, to a lesser extent, emerging market equities. The question is where we go from here. I think a broad-based restriction of Chinese investments is unlikely. The U.S. continues to target China on national security grounds, especially high-tech industries. If it’s targeted, we can still see strong fundamentals and earnings growth, as well as opportunities unimpacted by geopolitics. Longer term, this raises the question of decoupling as part of the deglobalization trend. I think it’s already happening to some extent. If deglobalization happens, emerging countries tend to be on the less favourable side because they benefit from outsourced manufacturing and global trade.

Keiller: A number of headlines have been quite flippant about a rapid decoupling, but the intricacies at play with these economies are vast. Annually, China and the U.S. trade roughly $600 billion—and about a quarter of China’s workforce is employed in sectors reliant on exports, with the U.S. being a large consumer. That said, one of the themes we’re thinking about within our positioning in China is the idea of self-sufficiency, which is becoming more important to the government and inherently linked to this. So in China, energy and semiconductors are two areas of interest.

If deglobalization happens, emerging countries tend to be on the less favourable side because they benefit from outsourced manufacturing and global trade.”

— Vivian Lin Thurston

Despite recent performance challenges, China has become a dominant weighting in the MSCI emerging markets index. Should it be carved out? Is there a deep and liquid enough pool of opportunities outside China for a diversified EM ex-China allocation?

Hingorani: We launched an EM ex-China product in early 2021 and we’re seeing interest from clients who are looking at this from different angles. Despite performance challenges, China is still 30 per cent of the index—double the weight of the next largest country. If you take A-share inclusion in China up to 100 per cent, then its weight in the index would be around 45 per cent. When a country becomes dominant like that in the past, investors start making discrete allocations to that country. China’s weight is only 3.5 per cent of MSCI market cap, but it accounts for 18 per cent of global GDP and 16 per cent of global market cap. This means China is fundamentally underrepresented in clients’ portfolios.

Keiller: There is a school of thought that suggests a manager dedicated to China could go deeper and further down the market-cap spectrum to find ideas—but this means an extra asset allocation decision for a client. Does the client want to make that decision themselves or rely on a manager? According to the feedback we’ve had from our client base, the answer is both. As to whether EM ex-China would be liquid enough, the short answer is yes. If you use $10 million in trading volume per day as a barometer, at least 400 stocks fall into that category. There’s a big opportunity there.

How does geographic and infrastructural resilience to climate change factor into your assessment of opportunities in these rapidly growing economies?

Keiller: Living conditions in emerging markets are already difficult and climate change could exacerbate these. Substitutes able to compete with fossil fuels have already emerged in areas like electricity generation, heating and road transport. Emerging markets play a big role in this, but substitution takes time. And remember there are Petro economies in emerging markets—some of which are reliant on the export of fossil fuels for their own trade balances. Brazil is one example here. We’ve made investments in traditional energy companies; and part of the investment case is that there will still be a place for relatively low-cost, low-carbon and reliable non-OPEC supply, even in a decarbonizing world.

Gravier: The main way we account for this is by understanding how each company we’re investing in deals with the impact of climate change, the materiality of it, as well as the governance and strategy around it. Part of the challenge is poor disclosure around the precise location of a company’s facilities, customers and suppliers when assessing their exposure to physical and transitional risks.

Hingorani: We look at this from a micro level, in terms of the questions we ask of management teams and the ESG demands made from the investor community. This feeds into the valuations we attribute to these companies because ESG is an integral factor to a company’s returns.

Living conditions in emerging markets are already difficult and climate change could exacerbate these. Substitutes able to compete with fossil fuels have already emerged in areas like electricity generation, heating and road transport.”

—Andrew Keiller

In terms of value versus growth investing approaches, how do you see the next decade shaping up for emerging markets?

Hingorani: We think the environment is very supportive for value investing. Despite value’s strong outperformance since late 2020, we still see extreme value dispersion in emerging markets. The premium the market is willing to pay for growth or quality stocks is close to historic highs. Over the last decade we’ve seen low inflation and rates, digitization and supply chain efficiency; and looking ahead to the next 10 years, we’re seeing higher inflation and rates, diversified supply chains, decarbonization and heavy capex—themes we believe are supportive for value investing. The long-term data shows that value investing outperforms in emerging markets.

Lin Thurston: There’s a high and positive correlation between value outperformance relative to growth and the 10-year yield in the U.S. But we do believe investors coming to emerging markets are looking for growth, whether from technological advancement or the rising middle-class consumer. Capturing those companies with long-term growth that translates into strong returns will be one important path to finding better companies. Growth is still attractive and the investment case for emerging markets remains unchanged from that perspective.

Snell: If you look at the data over the past 25 years in rolling five-year periods, it shows the fastest growing companies in emerging markets provide the best returns. It’s not a linear relationship—it’s exponential. We’re committed to finding those companies across the region; however, they can be across a range of industries—from cyclical commodity companies to rapidly growing ecommerce businesses. We’re agnostic to the type of growth and if the index providers characterize them as value or growth.

What value does active management in emerging markets offer for plan sponsors?

Lin Thurston: Emerging market equities have higher inefficiencies than a lot of other equity asset classes, which supports active management. Secondly, the composition of the indices does skew to some traditional industries. But now there’s a new economy of EM: consumer-driven, technology driven and digital-driven companies. This means active management is a valuable method to capture these new opportunities. In addition, EM countries are not shy of geopolitical, macro and policy considerations.

Keiller: When you look at sell-side analysts’ estimates from emerging markets and compare those to reality, you see that the sell side isn’t very good at predicting extreme outcomes. Looking at three-year earnings growth data starting in the late 1990s, we found 15 per cent of companies in emerging markets delivered over 45 per cent per annum earnings growth. That said, only about seven per cent of sell-side estimates captured this. That’s a big mismatch, evidencing a clear inefficiency you can exploit.

Hingorani: EM is a universe of more than 3,000 stocks from 25 countries with different drivers and many diverse return opportunities. It’s a universe that’s changing considerably. The weight of the Gulf Cooperation Council countries represents roughly six or seven per cent of the index, whereas they were only around one or two per cent five years ago. I went back and looked—and based on the eVestment universe index, which has about 500 managers, the index has come out in the fourth quartile over one, three and five years. And this demonstrates that active management works in emerging markets.

Emerging Markets Roundtable Sponsors

Baillie Gifford

Baillie Gifford is an independent investment partnership founded in Scotland in 1908. The fi rm focuses on long-term growth investing in some of the world’s most exciting companies and manages money on behalf of some of the world’s largest institutional investors, including 11 of the 20 biggest pension funds. For more information visit bailliegifford.com. As with any investment, capital is at risk.

Eastspring Investments

Eastspring Investments is a USD $228B (as of June 2023) global asset manager headquartered in Singapore and wholly-owned by Prudential plc. As “Experts in Asia”, we manage high conviction, global, regional Asia, and single country investment strategies for institutional and intermediary clients globally. Since our founding in 1994, we’ve built an unparalleled on-the ground investment presence in 11 key Asian markets and continue to expand our footprint and client engagements in North and South America and Europe. By leveraging our expertise operating and investing in the most diverse and inefficient markets in the world, we distinguish our firm by providing clients with differentiated perspectives, solutions, and outcomes.

For more information about Eastspring and our investment capabilities, please visit Eastspring.us

William Blair

Eighty-Eight Years as an Independent Investment Manager

William Blair is committed to building enduring relationships with our clients. As a fiduciary of institutional clients, we work closely with private and public pension funds, endowments, foundations, sovereign wealth funds, as well as other financial institutions. We are 100% active-employee-owned with broad-based ownership. Our experienced, investment teams are solely focused on active management and employ disciplined, analytical fundamental research processes across a wide range of strategies. William Blair is headquartered in Chicago with offices around the world providing expertise and solutions to meet our global clients’ evolving needs.

Intrinsic Strengths

In our view, the firm’s partnership structure, collegial and “client first” culture are critical factors to our success. These characteristics assist in attracting and retaining our seasoned investment professionals. With long-tenured portfolio managers and research analysts, our portfolios have been managed by some of the most stable investment teams in the world providing for consistent application and repeatable investment processes.

Diverse Thought Drives Strong Outcomes

• Diverse leadership teams: Investment Management led by women for over 20 years

• Received 100% score on the Human Rights Campaign’s Corporate Equity Index1 for the second consecutive year