With the #MeToo movement in full swing in recent months, criminal lawyer Marie Henein crystallized what needs to change at an event in Toronto recently.

“The baseline must be changed,” Henein, a criminal lawyer and partner at Henein Hutchinson LLP, said at a University of Toronto lecture in February.

“Women must be entitled to go to work, earn a living, walk down the street without being sexualized,” she added.

Read: What does the film industry’s #metoo moment mean for employers?

Much of the focus, of course, has been on high-profile cases of sexual harassment in the entertainment industry and the political sphere. But with the issues undoubtedly arising in workplaces of all types, what should employers be doing to respond to a new reality of zero tolerance for misbehaviour?

When an employee makes a complaint of sexual harassment, employers certainly have a moral duty and often a legal obligation to investigate the matter. Well before an incident occurs, however, employers should both develop policies and procedures that define harassment — including sexual harassment — and other behaviours that are unacceptable in the workplace and outline the steps they’ll take in response to an allegation.

“Organizations are permitted or empowered to take actions pursuant to their policies and in light of the laws,” says Kenda Murphy, a lawyer and workplace investigator at Rubin Thomlinson LLP in Toronto.

“The laws mandate certain things,” she adds. “Where the laws are silent on processes, that’s where organizations with good policies are able to make good decisions that follow those policies.”

So if an organization wants the option of putting one or both parties on paid leave, for example, it should ensure it has clearly written and widely disseminated policies that provide for that scenario.

Read: 60% of Canadians report experiencing workplace harassment: survey

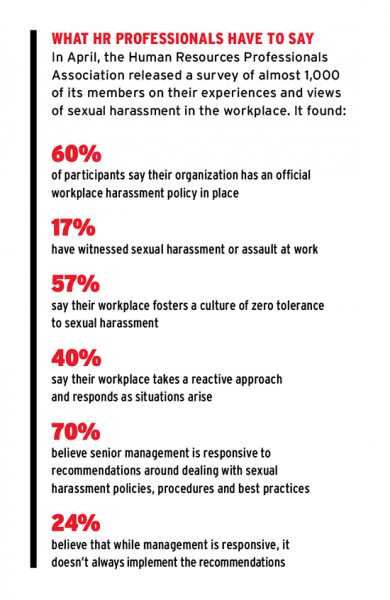

According to a public consultation led by the federal government in 2017, 76 per cent of Canadian workplaces have a sexual harassment policy and 65 per cent have one on violence prevention. But of the respondents who worked for such an organization, just 43 per cent received training on the former and 53 per cent on the latter.

For policies to be effective, all employees need to understand the protections they provide and the company’s expectations of them. Requiring employees to sign documents stating they’ve read and understood the policies in place can shield organizations from lawsuits, but to truly foster understanding, employers should invest in in-person training, according to Murphy. “It is really how people learn well because there’s an exchange,” she says. “You have someone leading the discussion, and that affords the [participants] the opportunity to ask questions and to get clarification.” Organizations with a significant number of remote workers can use video conferencing, she adds.

Training should address how employees can bring complaints forward, the process for investigating them and how it will protect the parties’ confidentiality, says Lauri Reesor, a partner at Hicks Morley Hamilton Stewart Storie LLP in Toronto. “Those are all really important things . . . so people feel safe coming forward with those types of allegations,” she says.

Legislation, of course, is a key consideration. According to Ontario government guidance on that province’s Occupational Health and Safety Act, employers have the option of using internal or external investigators to probe allegations of harassment, depending on the circumstances. “This initial decision [about hiring a third-party investigator] is something that employers are struggling with right now,” says Reesor.

Read: Federal government introduces bill to address workplace harassment, violence

The decision isn’t a bright-line test based on whether the alleged harassment was verbal or physical or on the number of parties involved. Employers should consider each complaint on its merits, although external investigators are essential for allegations involving senior executives or human resources staff. It’s also important for employees to be able to bring complaints to more than one person, so they don’t have to speak to their friend, boss or alleged harasser, according to Donna Marshall, co-founder of Workright Investigations Ltd. in Toronto.

Employers should also consider apps that allow employees to report workplace harassment anonymously, says Sonia Kang, assistant professor of organizational behaviour and human resources management at the University of Toronto. The app STOPit, for example, allows employees to report inappropriate behaviour and include text, photo and video evidence. It also allows managers to communicate with complainants anonymously.

While those accused of inappropriate behaviour have a right to know the details of the allegations, including the identity of the complainant, organizations need to act even if there’s no formal complaint or the employee doesn’t want to escalate the issue, according to Reesor. “The difficulty of these situations is that, legally, an employer does need to take it forward, once they’re aware,” she says.

“Employees need to understand that as well,” she adds, noting the importance of creating a work culture where employees feel they can come forward without putting their jobs in jeopardy.

Read: Parliament Hill staff call for closer look at workplace bullying: survey

Complaints about an employee from a member of the public are also an area of concern. “If the complaint is substantiated and the person was acting in the course of their employment, they can certainly be disciplined,” says Reesor.

Gathering the facts

Once an investigation begins, the first step is learning the details of the alleged interaction, says Marshall. That involves interviewing the complainant, alleged harasser and any witnesses and reviewing evidence such as emails, photographs and social media posts. At the end, investigators write a report outlining what happened, suggestions for responding to the incident and processes to help change organizational culture and ensure it doesn’t happen again.

Unless an employee is violent, Marshall recommends separating the parties by, for example, providing different shifts or offices but without terminating anyone before the investigation is complete. “If an organization can respond [to a complaint in a way that’s] respectful of both parties, then people feel much better about an investigation,” she says, noting the harm that can result when an organization responds before learning exactly what happened.

Read: 40% of employers take reactive approach to workplace harassment: HRPA

Reesor notes that putting the alleged harasser on paid, non-disciplinary leave is often a good solution. In addition to separating the parties while the investigation is ongoing, it encourages the employer to address the issue immediately.

Until the final report is complete, “the matter is open,” says Murphy, noting she’ll consider all information she comes across. She cautions, however, about the standard that applies. “It’s really important to understand that unlike the criminal context, where the standard of proof is beyond reasonable doubt, when we’re looking at the civil context . . . the standard of proof is balance of probabilities, which is a less onerous standard.” But even if the complainant and respondent present equally compelling versions of events, the matter may not reach that standard and the investigator could find the allegation to be unsubstantiated.

Murphy also notes some of the particularities of the various legislative provisions. In Ontario, for example, the legislation refers to harassment as “engaging in a course of vexatious comment or conduct against a worker in a workplace that is known or ought reasonably to be known to be unwelcome.” So if an employee filed a complaint after a colleague said something on the lines of, “Oh, you have a green sweater on,” the investigation would have to find the respondent knew or should have known the comment was unwelcome, which is unlikely.

“That’s not to minimize how the individual feels, whether he or she feels deeply that they have been harassed. But their evidence is always assessed against the definition and the balance of probabilities,” says Murphy.

Read: Tips for preventing sexual harassment in the workplace

If the investigation determines harassment did occur, employers should ask complainants what remedial action they’d like to see, according to Kang. Organizations have the last word on how they wish to proceed, but “not everyone is a Harvey Weinstein,” she says. “Not every experience of sexual harassment is at that level. . . . A lot of times, [complainants] just want an apology, to move on with their lives, for [the harassment] to stop. If you empower them to make a statement about the outcome they’re seeking, people might be more willing to engage in the process.”

Even decisions from administrative tribunals can be costly. While the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario generally awards damages ranging from $20,000 to $50,000, it can go higher. In one January 2018 case, A.B. v. Joe Singer Shoes Ltd., the tribunal awarded an employee $200,000, plus a decade’s worth of interest, after she alleged her manager had sexually harassed and assaulted her for several decades. Furthermore, workers’ compensation schemes in some provinces now include claims for chronic mental stress, including psychological disorders triggered by workplace bullying and harassment.

Dealing with the aftermath

Victims of prolonged workplace harassment and bullying can suffer from mental-health issues, including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, says Mark Davies, a Vancouver-area psychologist. Working hard, he notes, doesn’t help. “Bullies will typically punish the highest producers. The two main factors for how much stress we experience in our life are control and predictability, and when you’re in a bullying environment, both of those go right out the window.”

Read: N.S. human rights commission to help employers address workplace harassment

Even if an employer removes the workplace bully, victims don’t necessarily go back to normal right away. A good boss who has a bad day and snaps at them “can really send these people into a tailspin,” says Davies. “They’ve got to relearn not only how to trust the work environment but also how to trust their own radar, [which] has failed them so badly under the bully.”

Nevertheless, he cautions against relying on how employees respond to determine whether there’s a bullying situation. Some people are highly resilient and bullying may not affect their mental health, but that doesn’t mean the workplace behaviour is appropriate.

In some case, bullies may just have poor interpersonal skills and “can absolutely be rehabilitated,” says Marshall. In those cases, the bullies simply didn’t realize how their actions were coming across but can mend their ways once they receive training.

Davies, however, is less optimistic about bullies’ prospects for rehabilitation. He puts them in three categories — sociopaths, narcissists and stress bullies — and finds it highly unlikely the first two types can rehabilitate themselves. He also downplays the idea of solving the issue by sending someone to a training course. “That’s like saying, ‘I know you’ve got advanced leukemia, but I’ll give you two Aspirins.’”

Read: Tougher workplace harassment rules to apply to online spaces, says labour minister

Instead, Davies recommends isolating sociopaths and narcissists since they’re a better fit for remote work environments where they don’t have direct control over anyone.

There’s some hope for stress bullies, who simply can’t cope with the demands of their job and offload their tension onto junior workers, says Davies. While it can be difficult to rehabilitate a stress bully, it’s worth it, he argues. “It depends on what your value system is as an employer. If you really do value your employees, then of course you’d do that.”

Sara Tatelman is a Toronto-based freelance writer.