Squeezed by onerous funding requirements and overarching fiduciary duties, defined benefit plan sponsors are increasingly willing to embrace alternative structures — such as multi-employer pension plans, jointly sponsored pension plans and pooled registered pension plans — to relieve some of the pressure.

“Most employers simply shouldn’t be in the business of running a pension plan, and by moving into a JSPP or MEPP, they’re able to participate without the same responsibilities associated with running it themselves,” says Barry Gros, a retired actuary and board chair for the University of British Columbia’s staff pension plan.

However, these arrangements may never reach their full potential if regulators are stymied in their efforts, he adds, noting this could leave employers with fewer options when trying to get out of the DB game or making first-time savings offerings to employees.

Read: A look at the WSIB Employees’ Pension Plan’s conversion to a JSPP model

“Policy-makers have to get outside the old model, instead of trying to transpose it on top of the MEPP and JSPP space,” says Gros. “If they had a longer-term focus, they could come up with a different set of regulations that are much more conducive to growth in these sectors.”

So what’s the latest on MEPPs, JSPPs and PRPPs, and how can policy-makers, and the rest of the industry, ensure these plans reach their full potential?

Multi-employer pension plans

Particularly common in mobile and union-heavy fields, such as the construction and entertainment industries, MEPPs spread the risk of running a plan across a number of employers. Administrators have the ability to reduce accrued benefits when the balance between plan assets and liabilities get out of whack and the funded status takes a hit.

“I’m a big fan of the industry MEPP,” says Randy Bauslaugh, head of the national pensions, benefits and executive compensation practice at McCarthy Tétrault LLP. “They can provide retirement income to members on a much more cost-efficient, predictable and sustainable basis than any other way.

“The biggest advantage they have is that they don’t break, they bend,” he adds, recalling a MEPP run by a cross-border school association.

Read: A look at one of Canada’s oldest multi-employer target-benefit plan

Faced with a funding crisis precipitated by the 2008 financial crisis and compounded by rising life expectancy, the Canadian MEPP solved the issue by increasing its retirement age and slightly reducing benefits levels for some members. Meanwhile, the plan’s trustees in the U.S., boxed in by more rigid rules, were forced to convert it from a DB to a defined contribution arrangement.

Still, Bauslaugh laments the differential treatment that Canadian jurisdictions afford to MEPPs, and has assisted plan sponsor clients lobbying provincial governments for exemptions from solvency funding requirements already granted to union-sponsored MEPPs.

“I don’t understand why governments like Ontario and Newfoundland continue to discriminate against non-unionized workplaces,” he says.

For Susan Bird, president of third-party administrator McAteer Group, Canada’s considerable experience with MEPPs sends positive signals about the prospect of a comprehensive target-benefit regime across the country.

While progress on that front has been slow (federal Bill C-27 never progressed beyond first reading after vocal opposition from union groups), Bird remains optimistic about future developments. “Once we have legislation that is favourable to pension plans in the target-benefit space and the concept catches on, it’s going to inspire more MEPPs, and more employers who could be in MEPPs are going to wake up to the opportunities they offer.”

Jointly sponsored pension plans

A series of mergers are shaking up this pension category, which is characterized by an equal sharing of governance responsibilities between employers and employees.

The JSPP model is currently dominated by public sector plans, with the Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology pension plan, the OPSEU Pension Trust and the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System among the plans welcoming smaller, single-employer plans to join them.

Read: Ontario removes red tape for pension plans joining JSPPs

And in 2019, Ontario passed Bill 66, clearing the way for private sector plan sponsors to join existing JSPPs without the need for government approval.

Late last year, the final touches were put on the University Pension Plan, Ontario’s first freely collectively bargained JSPP, which brings together plans associated with faculty associations and locals of the United Steelworkers union at Queen’s University, the University of Guelph and the University of Toronto.

The arrangement provides peace of mind for all parties, says Alex McKinnon, head of research, policy and bargaining support at the union. “If sponsors have got a choice between going into a JSPP or an MEPP, or ending up with a DC plan, they have to go with the option that will best provide long-term retirement security. I’ve always believed that JSPPs and MEPPs are the future of pensions.”

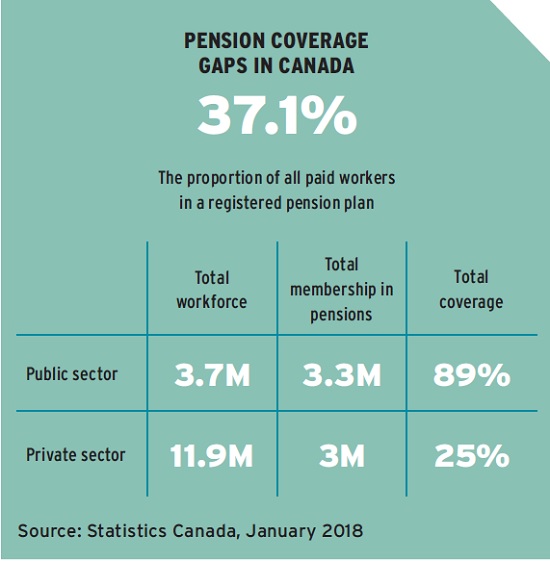

As exciting as these developments have proved to the industry, Gros says their impact may ultimately be limited. “We’re talking about consolidation within that minority of workplaces where employees are actually already covered by plans. The real big question is, who will step up to the plate and find a way to induce employers that do not have a plan to participate in any kind of scheme?”

Pooled registered pension plans

One potential solution to the coverage problem has so far fallen flat.

When Bill C-25 received royal assent in June 2012, making PRPPs available to those in federally regulated sectors, they were hailed as a low-cost alternative for self-employed individuals and workers at smaller businesses.

More than seven years later, most provinces — including B.C., Alberta and Ontario — have followed up with their own enabling legislation, but Gros says just a handful of PRPPs have actually made it to market.

Read: PRPPs continue to languish as provinces vary in enthusiasm for new option

“It was always a bit of a political compromise and I guess that’s what happens in those situations,” he says. “They don’t meet anyone’s needs and it just hasn’t worked.”

Matthew Ardrey, a portfolio manager and vice-president at TriDelta Financial, holds out little hope for a PRPP upturn unless something changes at various levels of government. “The concept is fine, but there’s no real reason for businesses to go out and do it.”

Even accounting for the small startup and administration costs of participating in a PRPP, the value of any talent attraction and retention is undermined by the portability of employees’ savings, he adds.

“There’s nothing stopping workers from leaving and taking their PRPP funds with them. The only way I could see employers going to the bother of getting involved in these plans is if there were some tax or other incentives for them doing so.”

Michael McKiernan is a freelance writer based in St. Catharines, Ont.