Faced with ballooning and unsustainable public pension liabilities, Taiwan’s government was forced to make a tough decision. In 2017, the country’s ruling Democratic Progressive Party passed a bill to dramatically cut retirement benefits for the country’s civil servants, public school teachers, police officers, firefighters and private sector workers.

The changes were unpopular, but necessary. Underfunded pension liabilities for public and labour sector pensions were expected to hit T$18 trillion ($830 billion) in 2016, a figure nine times the government’s annual budget expense, according to a report by Reuters. Government projections from 2017 showed Taiwan’s military pension was expected to default in 2020, followed by the private sector pension in 2027, the public school teachers’ pension in 2030 and the civil servants’ fund in 2031.

“Taiwan has a serious issue here,” says Ivy Kuan, Taiwan practice leader for retirement solutions at Aon. “Our issue is [very] desperate. It has to be changed and it has to be changed now.”

Read: How pension policy reform in Asia is addressing retirement income security

The bill, which took effect in July 2018, implemented wide-ranging changes. It increased the retirement age from 55 to 60 by 2021 and to 65 in 2026. It gradually lowered the income replacement rate over 10 years: plan members with 35 years of service will see a decrease from a 75 per cent income replacement rate to 60 per cent, while members with 15 years of service will see a drop from 45 per cent to 30 per cent.

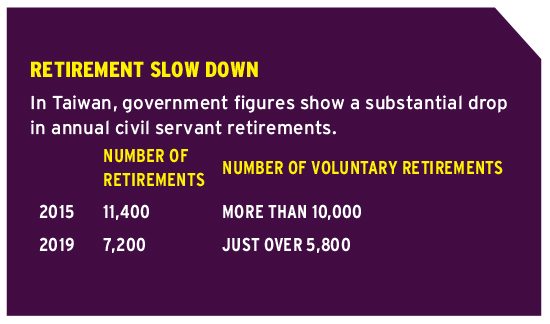

Taiwan’s pension changes

by the numbers

• Taiwan’s new legislation increased the retirement age from 55 to 60 by 2021 and 65 by 2026.

• Retirees with 35 years of service will see their income replacement rate drop from 75% to 60%. Those with 15 years of service will see their rate lowered from 45% to 30%.

• Plan members will also see their 18% government-subsidized interest rate on savings cut to 9% by Dec. 31, 2020 and to 0 by Jan 1, 2021.

It also changed how civil servants’ pensions are calculated, immediately moving from a formula based on a plan member’s salary in their last month of service to one that uses the average monthly salary in their final five years of service. Over 10 years, it will change again, to use a plan member’s average monthly salary during their final 15 years of service.

Retirees who receive T$32,160 ($1,484) or more per month will also see their 18 per cent government-subsidized interest rate on savings cut to nine per cent by Dec. 31, 2020 and to zero on Jan 1, 2021. And those who opted for a lump-sum retirement payment rather than a monthly pension will have their interest rate cut to six per cent over a six-year period.

Read: Canadian model offers lessons for U.S. public pensions: report

The changes “extended the timeline” before the public sector plans go bankrupt, says Kuan. It was good for them to do, but more is needed. . . . I do think there will be another reform to improve the system, but what [our government] did at the moment was something that at least gives us more room to grow and to think about further actions we can work on in the future.”

Pricing pension guarantees

Canada’s public sector plans aren’t anywhere near the same levels of unsustainability — and many are funded at levels above 100 per cent. But according to Malcolm Hamilton, a retired actuary who specialized in pension plan design and funding, these plans could still benefit from some, if not all, of the changes made by Taiwan’s government.

In a 2014 paper for the C.D. Howe Institute, Hamilton explored the true cost of public sector plans. While noting they were generally efficient, well-managed and their funding levels were healthy compared to private sector plans and other countries’ public sector plans, Hamilton said the pricing of pension guarantees has led to a difference between the fair value of these pensions and their cost according to the plans’ financial statements.

At the time, Canada’s public sector plans were recognizing reasonably expected returns from their investment risk before actually experiencing them and using those future returns to reduce the reported cost of plan members’ pensions, he argued. As a result, the paper said taxpayers were bearing the investment risk these plans were forced to take, while the rewards of those risks went entirely to public sector employees.

Read: PSAC calling for change to federal government’s public sector pension liabilities reporting

As well, the rate of return on safer investments, such as fixed income, has decreased substantially from 30 years ago with interest rates reaching historic and prolonged lows. By and large, public sector plans — which provide a “good but not reasonably so” income replacement rate of about 50 per cent, rising to 70 per cent when incorporating the Canada Pension Plan or Quebec Pension Plan and old-age security — haven’t responded to this reality with design changes such as more substantial contribution increases, benefit reductions, changes to the retirement age or to indexation policies, says Hamilton, noting they’ve chosen to take “heroic” investment risks instead.

While coronavirus-related market volatility in 2020’s first quarter depressed pension returns, Hamilton doesn’t expect to see provincial and federal governments looking at more radical reforms to benefits until they’ve experienced years of poor returns. But a prolonged negative market isn’t speculation, he notes; it’s a reality given the difference between what returns plan sponsors could expect decades ago compared to today and into the future.

“Short of a miracle, they’re not going to generate anything [in the next 30 years] like the returns we’ve grown accustomed to. They should be preparing for that, not just turning up 20 years from now shrugging their shoulders and saying, ‘Who could have foreseen that?’ This is very foreseeable. They should be acting on it. If they’re acting on it in Asia, good for them.”

Read: Taxpayers on hook for liabilities in federal staff pension plans: report

Chris Aylward, national president of the Public Service Alliance of Canada, disagreed. “Making significant reforms like forcing workers to retire later or pay more in pension contributions simply because we’re in a period of historically low interest rates is both short-sighted and irresponsible,” he wrote in an email to Benefits Canada.

“When interest rates inevitably rise again — as we’ve seen countless times before — the cost of providing the federal public service pension plan will decline once again. Pension plans are designed to forecast and account for economic changes far into the future, including dips in the economy.”

Shifting demographic

Todd Saulnier, chair of the Association of Canadian Pension Management’s national policy committee, says the early retirement age requires a re-think. “The reality is, we’re all living longer than we were 30 to 40 years ago, so it’s reasonable the retirement income period should be adjusted for how long you’re expected to live. It doesn’t make sense to participate in a program for 30 years and then get 40 years of retirement income.”

He expects to see this conversation continue in the context of the CPP. While the move to increase the retirement age to 67 was rolled back by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government in its first term, Saulnier expects it will increase again as Canada’s demographics continue to shift.

Read: Head to head: Is it time to change the retirement age?

“The shift to an older age profile of the population is happening much faster in Asia. . . . That’s what causes strain on the system, having a greater proportion of older [citizens] compared to the working population, particularly in pay-as-you-go [retirement systems] like Canada’s,” he says. “I do think the actions [Taiwain is] having to take are completely understandable. Just trying to make the system more sustainable is something each country is going to have to do based on needs.”

Canadian public sector plans must implement changes that reduce the risk to taxpayers and shift it toward plan members, says Hamilton, with the natural adaptation some combination of lower salaries, higher pension contributions, a later retirement age and possibly changes to contingent inflation protection.

Some pensions have already shifted more risk to members. Plans operating under a jointly sponsored model, such as the Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology pension plan and the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, make members partially responsible for funding deficiencies. As well, some plans have migrated to a target-benefit model that reduces benefits based on performance. And in June, the OMERS Sponsors Corp. board approved a move to shared-risk indexing, providing the plan with the option to reduce future inflation increases on benefits earned after Dec. 31, 2022, based on an annual assessment of its health and viability.

Read: OMERS Sponsors Corp. approves shared-risk indexing, other plan design changes

Ultimately, says Hamilton, it’s on plan sponsors, rather than administrators, to make the changes to keep these plans sustainable. “The changes need to be at the provincial government level, the ministry level, [during] the collective bargaining between employers and employees. . . . It’s not the chief executive officers of [these plans] who are responsible; it’s the ministers and the civil service, basically mismanaging public finance to a huge extent.”

Kelsey Rolfe is an associate editor at Benefits Canada.