In early 2020, many employees had no idea a great wave was on its way. While reports of a novel coronavirus spread around the globe, Canadians were still going about their days as usual — rolling out of bed, getting dressed and hitting the road for yet another humdrum day at the office.

By mid-March, things across the country had drastically changed. Many white-collar workers started rolling out of bed, maybe getting dressed and opening their laptops to work remotely. Meanwhile, a range of employees, from nurses to baristas to factory workers, suddenly found themselves deemed essential or frontline heroes who now put their health on the line every time they clock in.

Read: Employee mental health, productivity remain low amid pandemic

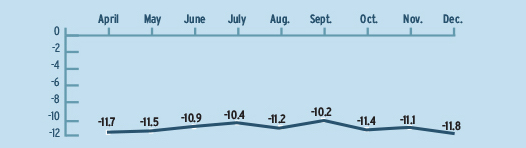

This seismic shift in working conditions has coincided with dramatic drops in employee’s mental well-being. Canadians’ mental health dipped at the beginning of the crisis, then rose as cases decreased in the summer only to decline again as the second wave walloped Canada this fall and winter. In December, employees’ mental health was at negative 11.8, due to the prolonged strain of the pandemic, found Morneau Shepell Ltd.’s monthly mental-health index. The monthly mental-health index has tracked Canadians’ emotional struggles since the pandemic was officially declared and is measured against a benchmark of data collected pre-pandemic, from 2017-2019. The stark numbers in the chart below show the mental health of Canadians’ stayed stubbornly low throughout 2020.

“Mental health has declined in a massive way,” says Paula Allen, the consultancy’s senior vice-president of research, analytics and innovation. “With the stress that we have, with the amount of change that we have, with the level of unpredictability, one would expect some level of impact on mental health, but this has been astounding how it’s declined.”

In response, employers have been stepping up with increasingly robust benefits offerings to support their employees’ throughout this once-in-a-century crisis. Almost a year later, many shifts brought on or accelerated by the pandemic — from increased virtual health-care offerings to programs that help working parents to more closely tracking mental well-being — are likely here to stay.

Supporting employees

Unilever Canada Inc. has a mix of white-collar employees, who are now working from home, and factory and supply-chain staff who are considered essential and continued to work in person since the pandemic hit.

“We are not unlike other organizations — our employees experienced fear and anxiety over the unknown of the pandemic,” says Bronwyn Ott, the consumer goods company’s head of North America well-being and culture, referring to the early days of the crisis.

Read: Women leaving workforce to care for kids during pandemic: report

“Work-life balance and blurred boundaries was a struggle for our people, particularly when schools and daycares closed and parents were managing online school, kids at home. . . . We initiated an incident management team right at the start, to ensure that we had a strategic approach focused on the health, safety and well-being of our people and business continuity.”

While Unilever didn’t see an increase in its employee assistance program usage at first, as the pandemic dragged on, it saw more employees using the EAP for concerns such as personal stress, she says.

Since March, the company has communicated regularly with its employees via town halls and meetings to ensure they “trust in our approach and feel that their well-being is a priority,” she adds, noting Unilever has backed those communications up with action.

For example, the company substantially strengthened its online offerings supporting mental well-being, primarily via a new virtual-care program, meditation app and a digital tool that provides mental-health assessments, matches employees with therapists and offers internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy. The company has also increased the amount in its lifestyle spending account and enhanced policies to assist employees with home office expenses, food delivery, personal protective equipment and charitable donations.

Read: How 5 employers are helping staff battle mental-health challenges

Since its launch, the organization has seen significant engagement in its virtual-care program and the well-being scores in its employee engagement survey have increased year over year, says Ott.

While rising well-being scores may not be expected during a global pandemic, research shows employers that invest in supporting employee mental health amid these tough times will reap rewards, says Allen. “Mental health has come out of the shadows and we’ve found that employers that did well [addressing employee well-being], their engagement actually went up — so [an increase] during a crisis, that’s a great thing.”

Benefits on a budget

For both employees and employers, the ongoing public-health crisis has resulted in financial worries, which also affect peoples’ mental health.

“With mental health, a lot of the anxiety with COVID is people having financial concerns,” says Margaret Eaton, national chief executive officer at the Canadian Mental Health Association. Liz Horvath, manager of workplace mental health at the Mental Health Commission of Canada, agrees money worries are a big driver of stress for staff.

Many employers are also facing financial challenges and there are many low- or no-cost options they can tap into, such as offering a webinar on dealing with financial stress or simply reminding staff of the benefits related to finances that are already in place, Horvath suggests.

Read: Using data to develop holistic workplace mental-health training

Key takeaways

• The mental health of Canadians has declined significantly since the beginning of the global coronavirus pandemic in March 2020.

• Employers will have to continue to support employee well-being by enhancing their benefits offerings throughout 2021

and beyond.

• Spending time and money on supporting mental health makes good business sense as it helps employers cut down on associated disability claims and turnover costs.

There’s also a host of free, government-funded iCBT offerings that have been introduced over the past 11 months that employers can highlight for their workforces. The CMHA, for example, launched a free, guided self-help program nationally in 2019. Morneau Shepell partnered with the Manitoba and Ontario governments to provide free mental-health support through its AbilitiCBT virtual platform. And last summer, the federal government introduced Wellness Together Canada, a free online offering that provides immediate mental health and substance use support for Canadians of all ages.

There’s plenty of resources available for struggling employees, but the first step for many employers is often identifying and then pointing people to help.

For example, Unilever has a network of mental-health champions who are trained in mental-health first aid and act as supportive, listening ears and advocates for creating a stigma-free workplace, says Ott. “As a result of COVID-19, . . . we design[ed] a virtual approach and increased the number of champions infused across the business. The training started in October and we already have 160 North American employees trained.”

Read: IBM Canada training managers to recognize mental-health red flags

It also provided line managers with a conversation guide that gives them advice on how to talk to employees about difficult topics like mental health. As well, the company began offering a variety of learning opportunities via webinars, trainings and town halls to help employees build resiliency, thrive through significant disruption and adapt to new ways of working. Throughout the pandemic, Unilever has also conducted sentiment and pulse surveys, using the results to pivot its efforts as needed.

One size doesn’t fit all

Many employers quickly pivoted in the wake of the pandemic, offering a bevy of online options to support employee well-being virtually overnight.

Dr. Marc Robin, medical director and telemedicine physician at Dialogue, predicts the shift to virtual offerings is here to stay. “The genie is out of the bottle so to speak. Just as not everyone is going to go back to working in offices, remote work will be a thing that’s present in our lives and so will virtual health care. . . . The pandemic has accelerated the use of virtual care and employers offering this to employees makes more and more sense.”

As the appetite for virtual offerings increases, Allen suggests these products be tailored to the specific needs of employees.

Read: Most Canadians say employer should offer virtual health care: survey

Working parents, in particular, are struggling to juggle their work and home demands these days and Unilever tailored a program to fit their specific needs. It launched an online virtual tutoring program in the fall to provide one-on-one tutoring alongside a number of other online supports for school-aged children. The company also strengthened its existing childcare program by offering coverage for personal supports due to closures of daycare centres and schools.

It also further enhanced several existing programs in response to the pandemic, including expanding the range of mental-health practitioners covered under its benefits plan to include marriage and family therapists, psychotherapists and clinical counsellors, provided employees with two additional days off to thank them for their commitment to the company and launched ‘U-time,’ which reduced core hours to help staff better manage the blurred boundaries between home and work.

Unilever’s investments in supporting employee’s overall well-being have paid off, with business results growing despite the pandemic, says Ott. “We put mental and physical health as equal priorities for our people right from the start. . . . We are proud and thankful of our factory and supply-chain colleagues, who demonstrated resilience and commitment throughout COVID-19 to maintain business continuity.”

Read: How Citigroup is using leave policies to support employees amid the pandemic

It’s a step in the right direction to see employers not only talking the talk, but walking the walk by putting more time and money into benefits to support workers’ well-being, says Eaton. When severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) hit Toronto in 2003, she recalls, people weren’t yet openly talking about the emotional impact of a public-health crisis, but things have changed. “Everyone has been struggling with isolation and loneliness and [some with] being at home while working from home. I feel there is less stigma this time; we’re not pushing it under the rug and saying ‘suck it up,’ which we have in previous situations.”

It’s not over ‘til it’s over

While Canada and the rest of the world now have access to multiple vaccines, it’s likely to be many more months until employees can go back to their pre-pandemic work routines. In the meantime, it’s key that human resources and company leaders don’t take their feet off the gas when it comes to providing employees with substantive support during now and in the years to come.

“I think the pandemic has really brought to the forefront that your business can’t run without people — and healthy people,” says Allen. “So if you don’t have that as part of your business plan, you’re going to be in a difficult place. If your people aren’t doing well, you’re going to have the turnover costs, you’re also going to have health and disability costs.”

Read: Serious mental-health crisis coming post-pandemic: poll

Even after the majority of Canadians are vaccinated, employee burnout and the subsequent costs associated with claims and turnover will still need to be managed. The true damage of a storm often isn’t clear until the rain and wind stops. Indeed, the impact of the emotional storms wrought by the pandemic will likely be with employees and employers for a long time yet, says Robin.

“In the psychological phases associated with a disaster — [which] certainly applies to this pandemic — there’s the initial impact, which was the heroic phase of going to Costco and filling up your basket.

Then came the honeymoon phase of comfort at home with food and family and thinking you’re going to be OK. Then you get into the big disillusionment phase that we’re in now and that can last years — that’s where the grind and the marathon of hardness kicks in.”

Melissa Dunne is the editor (interim) of Benefits Canada.