Despite significant improvements recently to pension plan solvency levels, the start of 2018 has been a challenging one for institutional investors. Shifting monetary policies have put pressure on bond portfolios, while rising yields have started to affect the equity markets.

On the equity side, the S&P/TSX composite index has gone from a high of almost 16,413 points on Jan. 4 to a low of 15,035 points on Feb. 9. The steepest drops came in early February, and while the index has hovered in the 15,000-point range since then, volatility levels have since subsided. As for the Dow Jones Industrial Average, it hit its 2018 high later in January but has followed a relatively similar pattern of a steep drop in early February and lower levels of volatility since then.

Read: Equity volatility exerts mild impact on pension plan health in first quarter

With volatility beginning to creep back into market consciousness, Justin Harvey, solutions strategist at T. Rowe Price Group Inc., worries institutional investors have gotten too used to the long run of upward momentum. There will be no room for complacency in the future, he says.

“I think it is a concern that we’re seeing institutional investors . . . across the globe with this sense of euphoria. It’s almost like . . . the recent bull run has replaced any memory of what happened previously,” says Harvey.

Risk, of course, is a key consideration in such an environment. Adding to the considerations is the current movement around pension solvency reform in many provinces that could cause plan sponsors to perceive the risks inherent in their portfolios differently. So what are the different risk scenarios institutional investors should be considering?

From 100 to 85

Among the provinces working on the solvency issue is Ontario, which has moved forward with a plan to lower solvency funding requirements to 85 per cent from 100 per cent. Practically speaking, that means the amortization payments plan sponsors previously had to come up with to fully address a solvency deficiency will instead need to bring the plan to the 85 per cent mark. Ontario has also introduced rule that will require pension plans to amortize payments to a going-concern deficiency over a period of 10 years, rather than the current 15-year time frame.

Read: Ontario rolls out several parts of new DB framework

Nova Scotia is considering a similar reduction to solvency requirements as one option for reforming its regulations for defined benefit plans. Quebec, of course, led the way on the issue in 2016, when it eliminated the solvency requirement completely in favour of going-concern funding only. Manitoba is also looking at options for reform.

Whether the reduced solvency requirements will be a welcome relief or an eye-catching temptation for Ontario plan sponsors is unclear, says Ross Servick, head of Canada at Schroder Investment Management Ltd.

Plan sponsors that are currently facing problems reaching the 100 per cent mark will likely appreciate the breather the change represents, he says. “That does allow you to have some comfort in volatility,” says Servick.

Indeed, plan sponsors that are cringing at the choice of whether to make a contribution to boost a struggling plan will be especially happy, he says. That sense of relief, however, isn’t necessarily a good thing, he adds.

“In the [U.S.] corporate space in particular, if you’re able to postpone making a contribution, you’re going to, which hasn’t translated into pension health.”

Read: A look at Sears’ U.S. pension prospects as Canadian windup ordered

Given his concerns, Servick believes pension plans in Canada should avoid postponing contributions and be careful to avoid the temptation to reach for higher yields to solve potential funding issues, especially in the current environment of low returns.

Nevertheless, the reduced solvency requirement will mean a significant amount of wiggle room for investors looking to expand their menu of investment options. While it does open the door to more choice, it’s a freedom plan sponsors should be cautious about, says Francois Pellerin, a liability-driven investment strategist at Fidelity Institutional Asset Management.

“Optionality is good in itself. It allows investors and plan sponsors to have a broader universe of things [they] can do. That’s true here, but that’s also a longer leash they can use to strangle themselves,” he says, noting riskier assets or strategies are only appropriate if they align with the plan sponsor’s underlying long-term goals.

Less-liquid alternative investments, for example, could appear to be more feasible given the increased flexibility of not needing to fund up to the 100 per cent mark, says Pellerin. Since such investments take longer to produce returns, they can be a challenge for plan sponsors that are trying to maintain high levels of solvency funding, he notes. The risk, according to Pellerin, is that “people will lock themselves into alternatives, and down the road it turns out what they wanted to do was terminate the plan and now they can’t because they don’t have the liquidity they need.”

Read: Pension plans showing positive results despite challenges for equities

As well, the perceived ability to weather more equity volatility could be a concern as the current environment suggests it’s a good time to exercise increased caution, he adds.

Besides possible shifts to the asset mix, the new framework could also influence other aspects of plan sponsors’ decision-making, says Derek Dobson, chief executive officer and plan manager of the Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology pension plan. Dobson, whose plan has been encouraging plan sponsors to consider merging with jointly sponsored plans such as his, notes the changes could affect decisions about whether to do just that.

“[Jointly sponsored pension plans] are still going to continue to work under their old rules, but the impact on us is that employers who might have otherwise been motivated to consider joining a multi-employer plan may have less pressure than they did before,” he says.

While CAAT, as a jointly sponsored plan, will be exempt from the new framework, Dobson says setting up further rules for specific plan types is a positive move. “I’m a big supporter of recognizing various types of risks and applying different funding standards to those various types of risk,” he says. “Now the challenge [that] clearly the government has faced is that they only have so many permutations they’re willing to entertain, based on different risk models. And as plans evolve, I think there’s more variety around risk models.”

The regulations giveth and taketh away

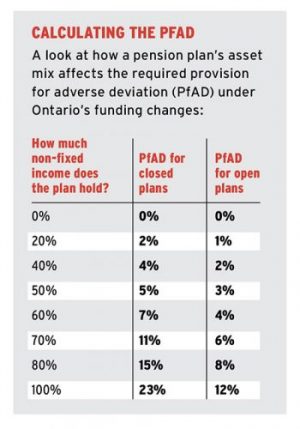

The second major change in the regulations may, conversely, create a more restrictive environment for pension investing and how plans account for risk. As part of the changes, Ontario is introducing a requirement to have a funding cushion, known as a provision for adverse deviation, to its pension rules. The provision includes three parts: a fixed requirement of five per cent of going-concern liabilities for closed plans and four per cent for open ones; a component based on the asset mix; and a third part reflecting the going-concern discount rate, should it exceed a certain amount.

Read: Ontario releases more details on funding cushion in new DB framework

For plans with a solvency ratio below 85 per cent, the worry over a potentially higher funding cushion will likely cause them to shift their asset mix towards more conservative investments, says Harvey. “But that would mean that the plan sponsor would have to accept the fact that because they’ve taken less risk in their investments, that they are going to have to fund the current shortfall,” he says.

When it comes to the more conservative side of the Ontario government’s investment framework for the funding cushion, investors are keen to know what it means when the regulations say bonds will “generally” fall into the fixed-income category, says Dave Makarchuk, a partner in the wealth business at Mercer. (In the regulations enacted in May, the Ontario government has since clarified that in order to fall into the fixed-income category for the purposes of calculating the funding cushion, bonds will need to have a minimum rating given by a recognized credit rating agency.)

Indeed, investors are waiting for a number of clarifications about the funding cushion, he says, noting the existing asset categories aren’t specific enough. “I’m just worried that when you only have three buckets, that there are things that should be in between the buckets and they just don’t have that option.”

Read: Ontario’s pension solvency framework should mirror Quebec’s new regime: ACPM

The Association of Canadian Pension Management raised several concerns in a January 2018 letter to the Ontario Ministry of Finance in response to the original regulatory proposals. The letter noted the government hasn’t denoted its specific motivation for implementing a funding cushion and strongly suggests it should make that intention clear. For actuaries, the ACPM argued, doing so would make it easier to calculate a plan-specific funding cushion that would directly build in the underlying policy objectives.

The ACPM also believes the government’s risk criteria for calculating the funding cushion are too broad and don’t go far enough in evaluating the risk profiles of distinct asset classes. They include alternative assets, which the government has categorized as 50 per cent fixed income and 50 per cent non-fixed income when counting towards a funding cushion.

Another concern with the funding cushion is the rules are somewhat unclear on how they define an open plan versus a closed one, according to a January 2018 letter written by the Canadian Institute of Actuaries to the government. Under the rules, an open plan with the same asset mix as a closed one would have a lower requirement for a funding cushion.

As an example of possible abuse of the definition to gain a lower funding cushion, the letter noted a plan would count as an open one even if it’s open only to 25 per cent of employees but closed to the remaining three-quarters of them. The letter, which suggested the policy might be an attempt by the government to encourage plans to remain open, questioned whether the approach would work and suggested plan status shouldn’t factor into the calculation of the funding cushion.

Read: Ontario announces long-awaited DB solvency reforms

Jason Vary, president of Actuarial Solutions Inc., agrees but concedes the government may have some other logic in how it defines open and closed plans. For example, a partially open plan would theoretically have a longer time horizon given its continued acceptance of new, younger members. As such, a lower funding cushion would be appropriate so the plan could take advantage of the longer time horizon to make somewhat more aggressive investments, he says.

May I have this dance?

With potential regulatory changes added to the discussion about the asset mix, plan sponsors will be considering whether to make allocation changes in a market that’s already proving to be difficult to read.

There are some implied signals about asset allocations within the rules for the funding cushion, says Makarchuk. The rules appear to discourage non-fixed-income investments comprising greater than 60 per cent of a portfolio since, if the percentage exceeds that amount, the funding cushion rises with them at twice the rate, he says.

Regardless of the government’s undeclared wishes, Makarchuk says it’s still possible to end up with the same funding cushion that would accompany a typical investment mix even with a very poorly constructed portfolio. For example, a pension fund with 40 per cent in cash and 60 per cent allocated to a single public cannabis stock would have the same funding cushion as a portfolio with a diverse 40/60 split between fixed income and equities.

Read: Currency considerations as plan sponsors grapple with volatility

So where will pension plans be eager to put their money with both current market conditions and the new rules in mind?

Pension plans have been on a “non-stop freight train going to private assets,” says Servick. Such investments are less of a roller-coaster for investors, partly because the average person can’t easily verify the price of private assets, as is possible with public ones, says Servick. “If there is a price discovery in [public] equities on a minute-by-minute basis, the more observations you have, the more volatility you’re going to experience.”

However, the changes to solvency funding requirements may mean Ontario pension plans will have more of a stomach for volatility from public equities, which could slow down the rush to get into the somewhat crowded area of private assets, he says.

Pushing the other way, from the perspective of both the funding cushion and in general, alternative assets like real estate and infrastructure look attractive, says Jafer Naqvi, vice-president of fixed income and multi-asset at Greystone Managed Investments Inc. “A lot of asset managers, us included, are trying to bring scalable solutions for DB plans — even the smallest ones — to access things like infrastructure and real estate within their asset mix, so even a plan as small as $10 or $20 million can find ways to access these vehicles,” he says.

The regulations recognize what Naqvi calls the “blended nature” of such alternative assets and thus splits them between the fixed-income and non-fixed-income categories.

Read: Preview of volatile 2018 as DB pension solvency dips in first quarter

Overall, markets may be heading towards a level of volatility that pension committees simply don’t have the nimbleness to navigate effectively, says Harvey. The volatility in the market perceived at a meeting that took place at the beginning of 2018 would have been very different from one held to wrap up the first quarter of the year, he notes. And with the infrequency of many committee meetings, plan sponsors can often shield themselves from the reality of a volatile market.

With increased volatility potentially contributing to a more risk-averse environment, the fact that investors are giving a nod to cash is a sign of how cautious investor sentiment currently is, says Harvey. As central banks in Europe, North America and Japan reduce the life support provided by their quantitative easing programs, the stability that investors turn to bonds for may be coming to an end, thus pushing them to hold more cash for longer than usual, he adds.

Choppy markets ahead

In order to navigate the choppier markets ahead, investors are going to need to be nimble, says Harvey, suggesting pension plans will need to pay close attention to macroeconomic concerns that could signal troubles on the horizon and strategize their equity allocations accordingly.

One concern is leverage. The combination of low interest rates and solid corporate earnings has, to some degree, blinded credit and stock analysts to the danger of how much leverage some companies have taken on, says Harvey. With interest rates on the rise, “should anything in the global economy . . . start to slow down and earnings slow down, that could be a recipe for a quick unwind of the gains we’ve seen,” he adds.

Read: Equity volatility exerts mild impact on pension plan health in first quarter

And with the U.S. and Chinese governments trading blows on the trade front, macroeconomic shifts aren’t hard to come by, he says, citing the potential for tariff battles to throw sand into the gears of global commerce and further harm corporate profits. “I think one of the things that we’re seeing a lot of interest in from sponsors globally, including in Canada, is for global equity mandates, as opposed to regional or sector-specific mandates, where essentially the investment manager has the flexibility to go across geographies, across sectors, across currencies for value wherever these market dislocations happen,” says Harvey.

In the meantime, investors are showing signs of pulling back from equities.

According to a survey released by BlackRock Inc. in January on institutional trends in asset allocation, 45 per cent of institutional investors in Canada and the United States plan to decrease their allocations to equities this year. But whatever the merits of that sentiment may be, Makarchuk offers some helpful perspective on the current uncertainties: “Can you remember a time ever, over the last 20 years, when there hasn’t been something to worry about?”

Martha Porado is an associate editor at Benefits Canada.

Download the charts from the Top 40 Money Managers Report.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the May issue of Benefits Canada, which went to press before the Ontario government enacted several of the new regulations on May 1. As such, the online version of the article reflects that development, whereas the original version in the May issue doesn’t.